Leonarduskerk Project (LKP)

Building community is to the collective as spiritual practice is to the individual.

FILE NOT FOUND

It Takes a Village

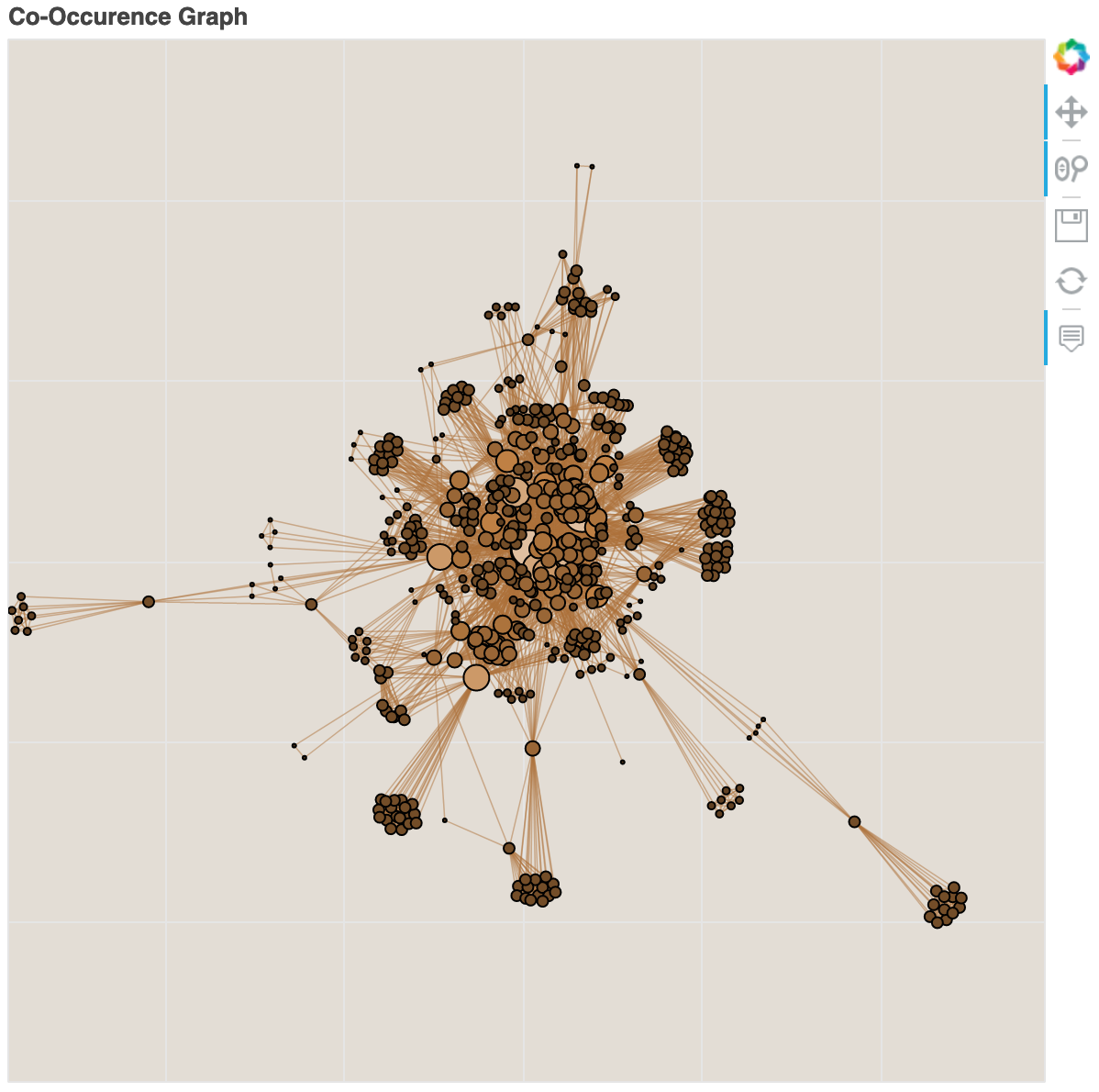

Building and maintaining a church requires the participation of the entire community.

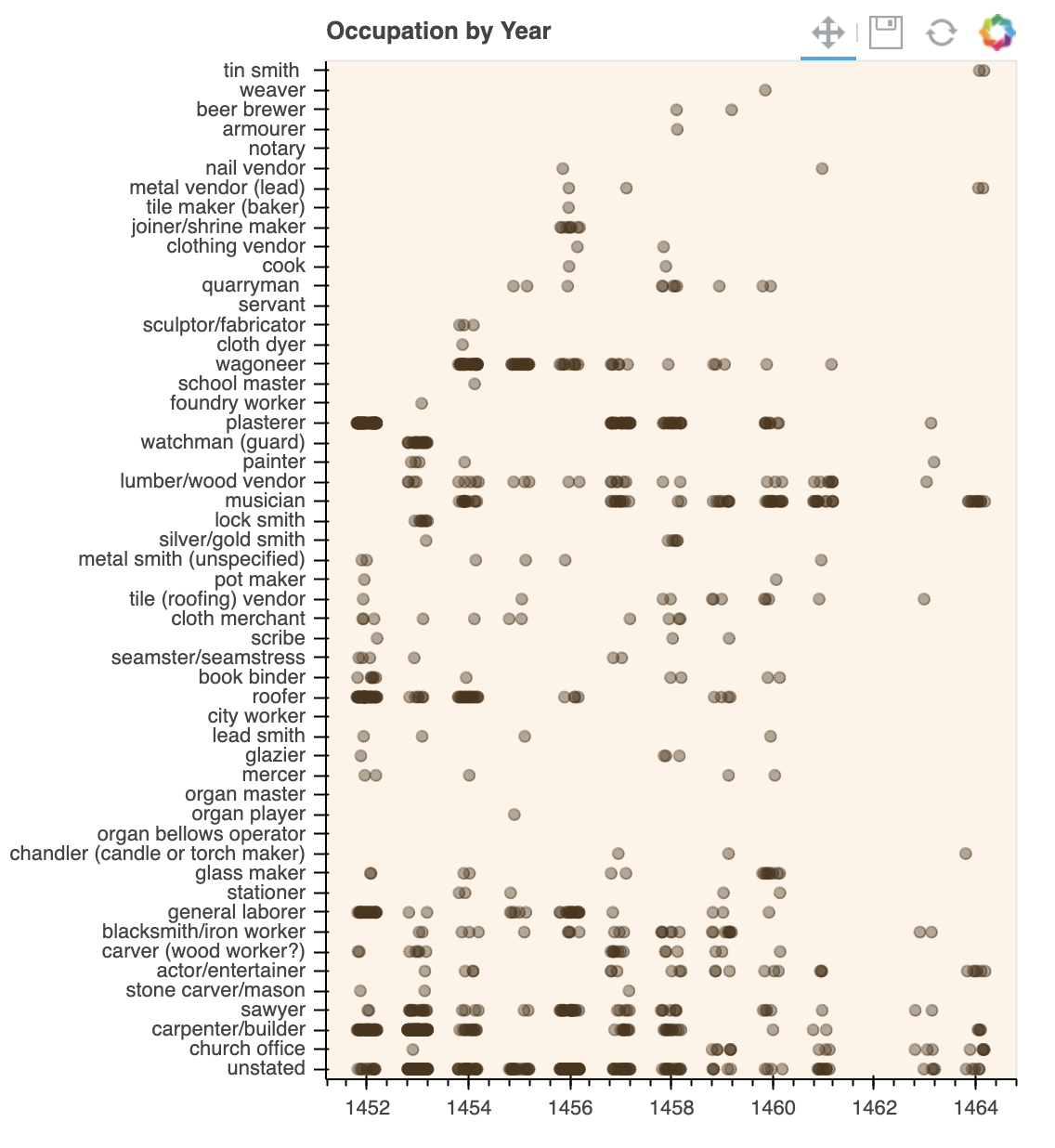

Planning and Coordinating

The various projects carried out on the church required planning and coordination.

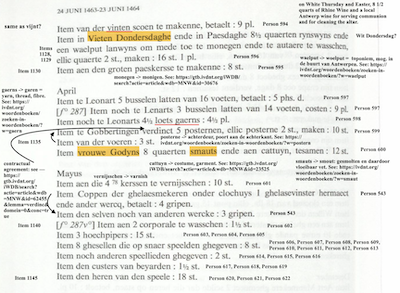

Lab Notes and Process

Studies like the Leonarduskerk Project require work and organization to come to fruition.